What We Need To Know About Probiotics

Probiotic is a scientific term defined as ‘living microorganisms, principally bacteria, that are safe for human consumption and when ingested in sufficient quantities, have beneficial effects on human health, beyond basic nutrition’1. This description has been accepted by the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

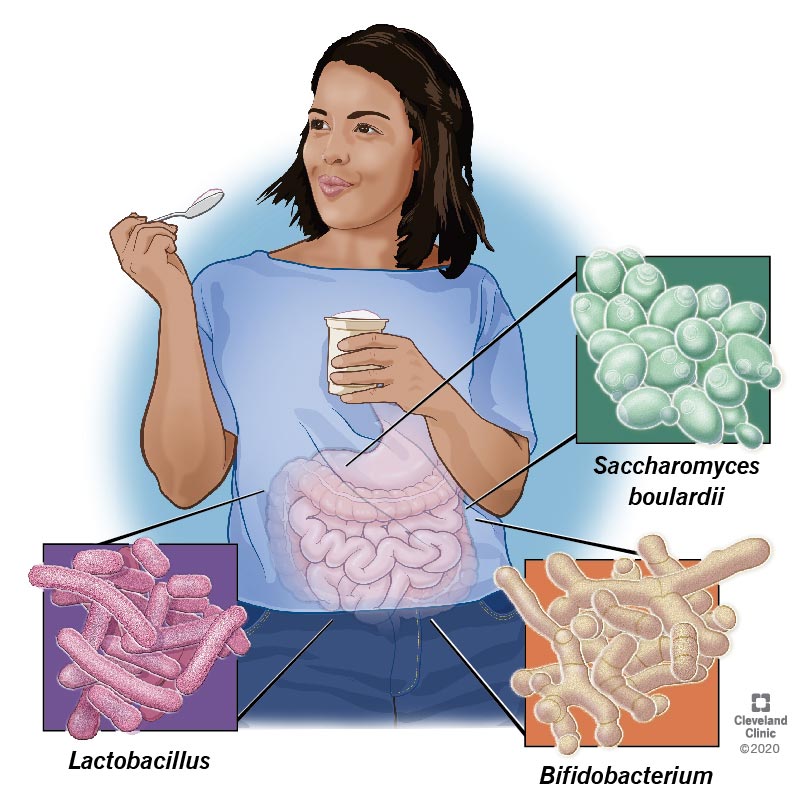

The Most Common Probiotic

The most common probiotic species belong to the genera Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus.

Lactobacillus species from which probiotic strains have been discovered and comprise of:

- L. acidophilus

- L. casei

- L. johnsonii

- L. gasseri

- L. rhamnosus, and

- L. reuteri

Similarly, the Bifidobacterium species include:

- B. bifidum

- B. infantis, and

- B. longum

Lactobacilli can yield many antimicrobial components, including hydrogen peroxide, organic acids, bacteriocins, low-molecular-weight antimicrobial substances, and adhesion inhibitors, and consequently have gained distinction as probiotics.2

When Were They Discovered?

These probiotics have been used for years in fermented products, but their medicinal use has not been formally recognized.3 Metchnikoff was the first researcher to mention that these microorganisms could provide health benefits and suggested that people in Bulgaria had a longer life span due to fermented milk containing this type of bacteria.

The term “Probiotic,” as contrasting to the term “antibiotic,” was originally suggested by Lilley and Stillwell in 1965, and the first probiotic species introduced in the scientific study was Lactobacillus acidophilus by Hull et al. in 1984 and then later Bifidobacterium bifidum by Holcombh et al. in 1991. 4

The World Health Organization in 1994 believed that probiotics are the next-most essential immune defense when commonly approved antibiotics are found useless due to the growing antibiotic resistance. These occurrences paved the way for a fresh concept of probiotics both in dentistry and medicine.4

How Do They Work?

The mechanism of action of probiotics differs according to the specific species or combinations of species used and the extent of the disease course in which the probiotic is administered.

Common suggestions are developing in research on how probiotics work, and many mechanisms have been recommended, including the following.

Prevention adhesion, colonization, and biofilm formation of the disease-causing microorganisms

Initiation of the activity of cytoprotective proteins on the surfaces of human cells

Non-production of an enzyme called collagenases and decreasing inflammation-associated components.

Boost of the human’s immune system and control of cell proliferation and cell death

Killing of disease-causing microorganisms through increased production of bacteriocins, acids, peroxide, or other products which are aggressive against these microorganisms

Modification of the surrounding environment inside the human body by controlling the oxidation-reduction potential and/or pH, which may affect the capacity of the harmful microorganisms to thrive

What Are Their Known Benefits on Children?

The safety and efficacy of probiotics in decreasing the duration of acute enteritis in pre-schooler children and decreasing the frequency of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm babies were confirmed. There are also some proofs supporting the use of some probiotics to either avoid or treat Clostridium difficile infection and antibiotic-associated diarrhea.

These data have been proven to be promising. Still, however, it is needed to approve the effectiveness of probiotics, either by monotherapy or in combination, in treating allergic enterocolitis and various chronic inflammatory bowel diseases.

What Are Their Known Benefits on Adults?

Probiotics may be beneficial in preventing antibiotic-induced diarrhea, including those triggered by C. difficile infection. They also decrease the severity and period of other adult diarrhea, specifically those caused by rotavirus. But, their part in preventing traveler’s diarrhea is still vague and bounds their usage in this said condition.

Scientific evidence for their efficacy in acute and chronic conditions specifies cumulative evidence demonstrating that probiotics are an effective part of combination therapy in treating Helicobacter pylori infection, showing improved eradication capacity and reductions in side effects. Though probiotics have shown promising results in improving symptoms related to irritable bowel syndrome, existing medical practice plans do not acclaim their use in treatment procedures.

In inflammatory bowel diseases, results are still vague, although benefits have been presented, especially in preventing relapses in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. It also has the most reliable and promising result in the treatment and/or prevention of pouchitis.

Evidence for the prevention of colorectal cancer in high-risk persons still requires long-management clinical trials. There is promising evidence in animal studies and some proof in the clinical setting that probiotics can reduce cell growth in patients with colonic adenoma. Other studies also proposed that marked improvement may occur in individuals with hepatic encephalopathy due to decreased fecal urease expression and blood ammonia levels.

What May Be The Future of Probiotic Studies?

Probiotic species are likely to be selected for clinical practice based on their underlying mechanism/s of action shortly. There is also the probability of emerging specific types of probiotics that are disease-targeted. Furthermore, time of ingestion, optimal dosages, maintenance of viability, single versus combination formulations, and the evidence of using probiotic-derived products still requires additional research.

Trending Health Topics

- ADHD

- Allergies

- Arthritis

- Bipolar Disorder

- Bunions

- Car Accidents

- Chron's Disease

- Common Cold

- COPD

- Depression

- Dry Skin

- Dry throat

- Eczema

- Fungal Infection

- GERD

- HIV/AIDS

- Hypertension

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Osteoarthritis

- Psoriasis

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Skin Disorders

- strep throat

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Uncategorized