Outer Ear Infections: Do You Know How Docs Diagnose It?

Inflammation or infection of the outer ear is commonly called Swimmer’s ear or otitis externa. Outer ear infections affect the outer ear, and the tube connecting the ear’s opening to the eardrum is called the tympanic membrane.

It typically affects children, swimmers, and those who use cotton swabs, hair sprays, hearing aids, and headphones.

Every year outer ear infections account for around 2.4 million visits to the doctor in the USA and approximately half a billion dollars in healthcare costs.

What Causes an Outer Ear Infection?

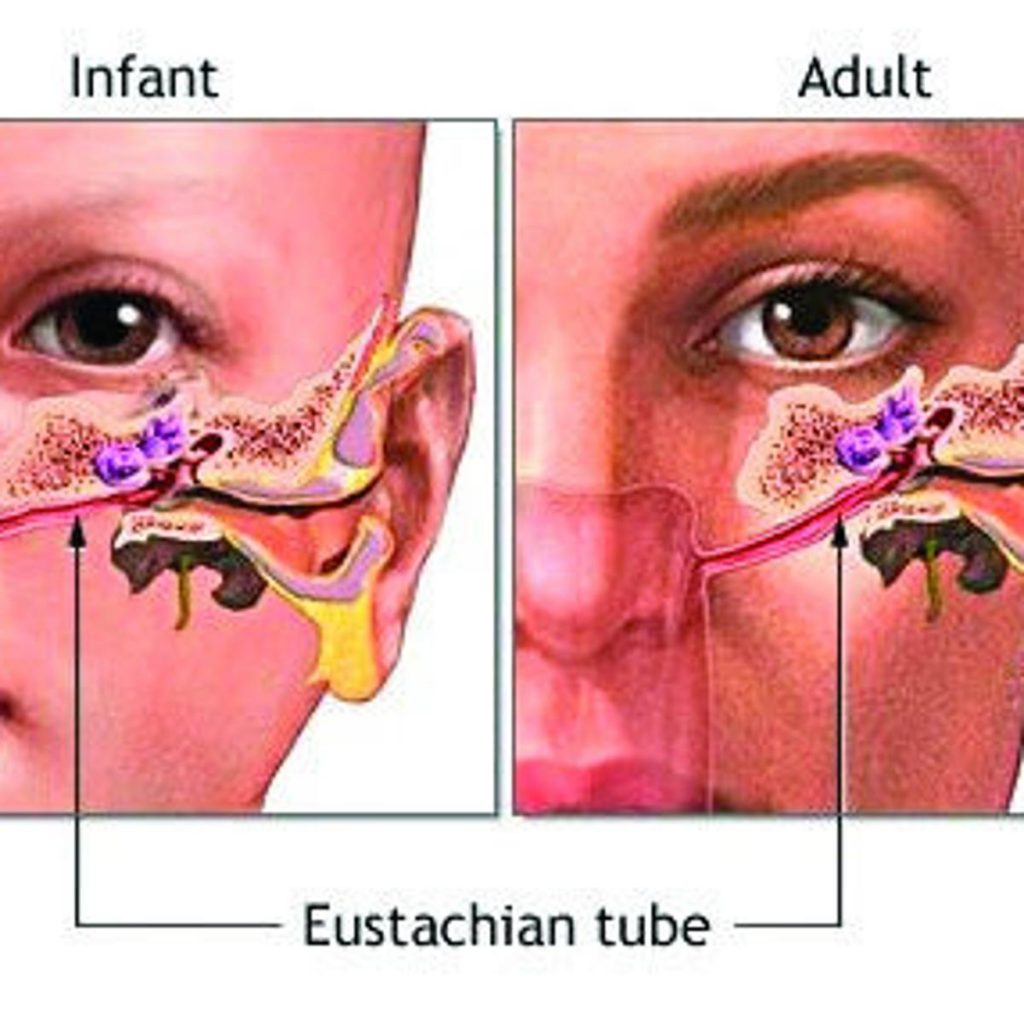

Water or damaged inner ear skin becomes a breeding ground for bacteria or fungi. It is not a big deal in most cases, as the eardrum or tympanic membrane prevents the infection caused by these organisms from reaching the middle ear or otitis media or the inner ear or labyrinthitis. The eardrum in the middle separates the outer ear from the inner ear.

The short-term outer ear infections referred to as acute otitis externa is prevalent most widely. Outer ear infections become chronic if they last for longer periods of 3 months or more.

Though not as common as acute otitis externa, very severe infections can occur in people who have diabetes or are immunocompromised. They are called malignant (necrotizing) otitis and affect the bone and surrounding tissue.

How Do Doctors Diagnose and Outer Ear Infection?

Understanding the patient’s history through a few simple questions and a physical examination is usually enough to diagnose during the first visit to the doctor.

In most cases, there’s no need for elaborate laboratory testing unless the infection has progressed and become chronic.

Patient’s History

The doctor will ask questions about the patient’s recent water-based activities such as swimming, diving, or surfing and any history of ear injury or ear trauma caused by earbuds or the insertion of blunt or sharp objects in the ear. The doctor will enquire about symptoms such as pain, itching, diminished hearing, and other signs of discomfort such as a mild fever, pus discharge, or a foul smelly fluid oozing out of the ear.

The physician may ask questions on aspects of diabetes, skin disorders, or previous ear surgeries, or radiotherapy, if any.

Physical Examination For Outer Ear Infections

The doctor will move on to a physical examination next. He will push the ear’s small exterior flap of skin inwards or pull the earlobe out gently. Any resulting pain from the pressure applied or the tug is a possible sign of outer ear infection.

In addition to checking the external part of the ear – the auricle or pinna for signs of swelling – many doctors will also take the precaution of checking the face for signs of facial nerve paresis and the neck and head for lymph nodes and cranial neuropathy.

At the next stage, the doctor will use an otoscope instrument to look for telltale signs inside the canal of the outer ear and the eardrum. He will look for swelling or redness in the ear canal. In the case of children, there could be obstructions like broken pieces of toys, beads, twigs, or insects in the ear canal. The presence of yellowish pus is indicative of bacterial infections. Fungal infections usually result in grayish-white pus. Often, the presence of pus, skin flakes, and ear wax block a clear view of the eardrum. He will use a suction device that gently sucks out this debris for a more unobstructed view of the eardrum.

If there’s nothing serious noticed in the initial check of the ear canal and eardrum, the patient will be treated empirically, without any diagnostic tests.

The doctor may decide on a further investigation through lab tests if the patient does not respond to the initial treatment or a ruptured eardrum with fluid draining out of it.

Lab Tests For Outer Ear Infections

The doctor suggests lab tests to identify the specific bacteria, fungus, or virus responsible for the infection if the patient is not responding to the initial treatment. The test involves collecting a sample of the fluid from the infected ear using a cotton swab. The sample is gram-stained and cultured for days in culture media for signs of organism growth. Identification of the organism helps the doctor select the most effective course of treatment.

In diabetics and patients who have compromised immune systems, it may be necessary to order some additional diagnostic tests. These include blood tests and a urine test.

Further Testing to Differentiate Outer and Middle Ear Infections

Sometimes, further testing is required to distinguish outer ear infections from middle ear infections as a different treatment may be needed, especially if the eardrum is damaged or torn. An ENT specialist or otolaryngologist uses a pneumatic otoscope to push air against the eardrum to assess the movement of the membrane and examine all parts of the eardrum. Problems in the middle ear see the use of pneumatic otoscopy and tympanometry.

In diabetics or the immunocompromised, the otolaryngologist must rule out necrotizing or malignant otitis externa.

Imaging Studies and Outer Ear Infections

In most cases of outer ear infections, imaging tests such as high–resolution Computer Tomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), and Bone Scans are not required. However, imaging is necessary where necrotizing or malignant infections are suspected. CT is preferred where one suspects bony erosions and MRI in the case of soft tissue problems.

Differential Diagnosis

Many conditions can be confused with outer ear infections. For example, though malignant tumors are rare in the ear canal, they could happen. The Journal of Clinical Microbiology also reports the uncommon and surprising case of moving worm-like organisms in both outer ear canals of a 38-year-old male patient.

Doctors must use all the physical evidence and diagnostic tools at their disposal to identify these challenging cases of outer ear infections and avoid misdiagnosis.

Trending Health Topics

- ADHD

- Allergies

- Arthritis

- Bipolar Disorder

- Bunions

- Car Accidents

- Chron's Disease

- Common Cold

- COPD

- Depression

- Dry Skin

- Dry throat

- Eczema

- Fungal Infection

- GERD

- HIV/AIDS

- Hypertension

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Osteoarthritis

- Psoriasis

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Skin Disorders

- strep throat

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Uncategorized